The Kunsthalle Bielefeld is presenting a comprehensive survey of German Impressionism, an art movement that spread throughout the entire country. Starting with the major Berlin artists Max Liebermann, Max Slevogt, and Lovis Corinth, the show ranges over the many northern, eastern, southern, and southwestern variations of German Impressionist painting.

Distinctions will be drawn between German and French Impressionism, and viewers will come to see that German Impressionism was an independent modern movement and a forerunner of Expressionism. The Bielefeld show will feature works on loan from such museums as the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, the Kunstmuseum St. Gallen, the Neue Pinakothek in Munich, the Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, the Hamburg Kunsthalle, the Saarland Museum in Saarbrücken, the Galerie Neue Meister in Dresden, and many other public and private collections.

Distinctions will be drawn between German and French Impressionism, and viewers will come to see that German Impressionism was an independent modern movement and a forerunner of Expressionism. The Bielefeld show will feature works on loan from such museums as the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, the Kunstmuseum St. Gallen, the Neue Pinakothek in Munich, the Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, the Hamburg Kunsthalle, the Saarland Museum in Saarbrücken, the Galerie Neue Meister in Dresden, and many other public and private collections.

The Revolution in Art

The modern revolution in art began in France. In Paris in 1874, Claude Monet and a group of young, progressive artists exhibited a scandalous painting, whose title described the contents of the picture exactly: L’impression, soleil levant (Impression, Sunrise). Critics used the painting’s title as invective, but artists adopted it for their new program. Instead of imitating nature, the goal of the Impressionists was to paint what they saw. With clear colors and small brush strokes, Impressionism was the first modern artistic revolt against the dark hues of the established, formalist, academic painters of the late nineteenth century.

German Impressionism

It took a good ten years for the new artistic atmosphere to influence attitudes throughout Europe. In Germany, the new approach to painting collided with the Empire’s rigid, conservative taste in art. Still, it quickly found its defenders among the German artists who resisted the academic standards and the kind of art the Kaiser himself officially demanded—an art that was essentially oriented toward historical paintings glorifying the Empire.

Max Liebermann, Lovis Corinth, Max Slevogt, and their fellow artists in the newly founded Berliner Secession took on the established academy. With their new works, they became the major representatives of Impressionism in Germany. Elsewhere, artists such as Thomas Herbst in Hamburg, Christian Landenberger in Stuttgart, Fritz von Uhde in Munich, Gotthard Kuehl and Robert Sterl in Dresden, and many others characterized the image of German Impressionism, which became established in the 1890s as the first modern movement in Germany, and, to a great extent, as a further development of the academic plein air painting.

Distinct from the French

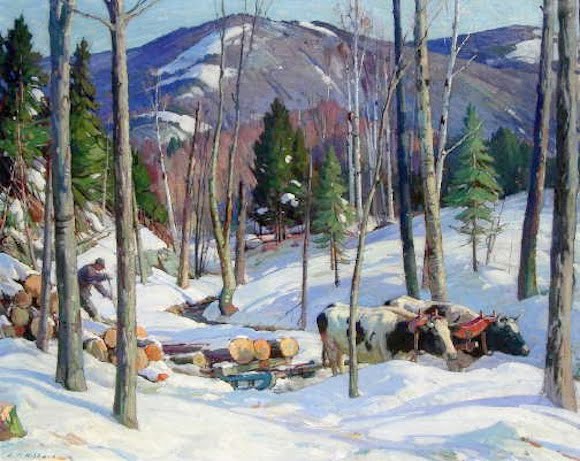

While Impressionism in France—with its emphatically bright, “enlightened” nuances of color—was considered an artistic expression of the joy and pleasure in life felt by a stronger, self-confident, and increasingly wealthy bourgeoisie, German Impressionism accentuated completely different things. “French lightness” was contrasted with “German heaviness,” expressed through a somewhat darker palette, a closed visual form, and a different selection of themes. Besides turning to nature and intimate family interiors, German artists also painted scenes from the working world and the everyday life of the less privileged classes. The Kaiser himself, probably with no less an artist than Max Liebermann in mind, reviled this kind of work as “gutter art.”

Containing a breathtaking variety of motifs and styles, the exhibition makes it possible to experience German Impressionism as the mirror of a strife-ridden period between the Empire and the Weimar Republic, between academicism and individuality. At the same time, viewers will find a cornucopia of familiar and unfamiliar works.

Open November 22, 2009 – January 31, 2010

www.kunsthalle-bielefeld.de

Image: Max Slevogt, Dame am Meer (Lady at the seaside), 1907. Oil on canvas, 75 x 58 cm. Kurpfälzisches Museum Heidelberg